View Post [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Jan 25, 2011 9:58am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead - FM Radio shows |

Grateful Dead shows - FM Radio broadcasts (updated)

DeadHeads should respect Edwin Armstrong's contribution to our listening pleasure. We should be thanking this gentleman for all FM broadcasts - whether they are simulcast live, or they are tape-delayed and played back later. Light into Ashes and others produced a list of The Dead's FM broadcasts. There were dozens of Dead shows on our FM radios. Let's respect this man's historical contribution. In 1933, Edwin H. Armstrong secured four patents which were to be the basis for frequency modulation (FM radio). This was an entirely new system of broadcasting. Unlike amplitude modulation (AM radio) which varies the amplitude or power of radio waves to transmit sound, frequency modulation varies the number of waves per second over a wide band of frequencies. As static is transmitted by amplitude modulation and cannot break into the wide band of frequencies of frequency modulation, the latter is virtually static–free. Armstrong, who enjoyed aphorisms, liked to quote defeatists who said, “Static, like the poor, will always be with us.” He proved them wrong.

Edwin H. Armstrong is The Father of FM Radio

Major E. H. Armstrong

December 18, 1890 – January 31, 1954

Atop the Palisades at Alpine, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from Yonkers, stands a tall, three–armed tower. It is accepted as part of the landscape by those who live on the river’s east bank and is seen daily by thousands of commuters on Conrail’s Hudson Division trains, yet few know what this tower is or how it has affected their lives. The tower and its accompanying radio station were built in 1938 at a cost of over $300,000 by Edwin Howard Armstrong, pioneer radio inventor, to demonstrate the superiority of his new system of radio broadcasting—frequency modulation (FM). After Promethean battles with the broadcasting industry, which fought to preserve its investment in the established system (amplitude modulation—AM), FM was finally accepted and today is the preferred system in radio, the required sound in TV, and the basis for mobile radio, microwave relay, and space communications. As little known as the significance of the tower is the man who built it. Armstrong was born in New York City in 1890. When he was twelve years old, the family moved to 1032 Warburton Avenue—known to family and friends simply as “1032” in Yonkers. The house, which still stands just up from the Greystone railroad station, was declared an historical landmark in 1978 by the Yonkers Historical Society. Next door, on the north side of the house at the corner of Odell Avenue, was 1040 Warburton Avenue, the home of Armstrong’s maternal grandparents. The members of the two families were a gregarious lot, and Howard’s childhood was a happy one filled with large gatherings of relatives, many of whom were teachers. Learning was prized. “Quick, boy! How much is nine times five, minus three, divided by six, times two, plus nine?” His great uncle, Charles Hartman, principal of New York City Public School 160 would quiz his nephew to encourage his mental agility. When Howard was fourteen years old, his father who was American representative for Oxford University Press, bought him (on one of his yearly trips to London) a book, The Boy’s Book of Inventions. Reading of Guglielmo Marconi’s sending of the first wireless message across the Atlantic so excited his imagination that he determined then and there to become an inventor. In his attic room in the cupola overlooking the Hudson River, Howard Armstrong began tinkering with radio. In those days, broadcast sound consisted of Morse code signals picked up with earphones. The incipient young inventor set out to make them louder. He was dogged in his search and developed at this early age a capacity for infinite patience in his experiments which was to mark his life’s work. “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety–nine percent perspiration,” he used to say in later years, quoting Thomas Edison. Armstrong explored many paths in his attempts to strengthen the sound. Reaching up into the air to better catch the broadcast signals, he flew from the upper stories of 1032 large antenna kites which he had built with the help of his Yonkers friend, Bill Russell. He built a 125–foot antenna pole, the tallest in the area, in the south yard. His younger sister, Edith (“Cricket”), helped in the construction, holding the guy wires and handing him buckets of paint as he swung aloft in a boatswain’s chair. Neighbors watched with awe and apprehension. His mother, however, had complete faith in her son. When a neighbor telephoned to say that Howard was at the top of the pole and it made her nervous to watch, “Don’t look, then,” was her reply. Howard attended Public School 6 in Yonkers and Yonkers High School, and went on from there to Columbia University, commuting on a red motorcycle his father had given him as a high school graduation present. His interest in radio led him to the study of electrical engineering. In his junior year at Columbia, Armstrong’s diligent search for improved radio reception paid off. He invented the regenerative–oscillating, or feedback, circuit which greatly increased radio signals, made them loud enough to be heard across a room and led the way to transatlantic radio telegraphy. His sister, Ethel, remembers vividly the night it happened. “Mother and Father were out playing cards with friends and I was fast asleep in bed. All of a sudden Howard burst into my room carrying a small box. He danced round and round the room shouting, ’I’ve done it! I’ve done it!’ I really don’t remember the sounds from the box. I was so groggy, just having been wakened. I just remember how excited he was.” Later, another inventor, Lee DeForest, challenged Armstrong’s priority for this discovery and the issue was twice argued before the US Supreme Court—which found in DeForest’s favor. However, the scientific community has always credited Armstrong for the invention and he received a gold medal for it from the Institute of Radio Engineers. Years later, the report accompanying the presentation to him of the Franklin Medal, by the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, also credited him with the invention of the regenerative circuit.

After graduation from Columbia in 1913, Armstrong worked as an instructor at the college. When the US entered the war in 1917, he joined the Army Signal Corps and rose to the rank of Major—his preferred title for the rest of his life. While in the service, he invented the super–heterodyne circuit which amplified even further the sound of radio transmission. This invention brought him into contact with David Sarnoff, who became President of Radio Corporation of America and whose bright and attractive secretary, Marion Maclnnis, Armstrong later married. After the war, Armstrong returned to Columbia where he worked as an assistant to Professor Michael I. Pupin, famed physicist and inventor. (Ed.note: Pupin lived at 7 Highland Place in Yonkers.) When Pupin died, Armstrong took over his professorship and, financing his own research—his inventions had by now made him wealthy—concentrated on the elimination of static. The first public broadcast of FM was made in 1935 from the home of his friend C.R. (Randy) Runyon at 544 North Broadway in Yonkers. Runyon was a ham who operated under the call letters W2AG and broadcast from a tower in the yard of his house. The tower and the house are no longer standing. The Runyon living room served as a studio for a demonstration of different kinds of sound that were broadcast to a meeting of the Institute of Radio Engineers at the Engineer’s Building on West 39th Street in New York City. Water was poured, paper was crumpled, and live and recorded music were beamed from the Runyon tower to the audience forty miles away. Although the engineers marveled at the fidelity of the sound, FM did not immediately take off and it would be some time before it would become a commercial success. “If you build a better mousetrap the world doesn’t necessarily beat a path to your door,” Armstrong said ruefully in later years as he fought for the acceptance of his new system of broadcasting. As a matter of fact, FM was so revolutionary that an entire industry had to scrap its hardware and start over before its potential could be realized. Understandably, the establishment was less than enthusiastic at the prospect.

However, for several years RCA gave Armstrong experimental broadcast privileges in its studio at the top of the Empire State Building. But in 1937, saying that they wished to devote the space to the development of TV, they asked Armstrong to withdraw. More determined than ever to prove the superiority of FM, Armstrong built his own station in Alpine, New Jersey. The site he chose had been visible to him as a boy from his attic cupola at 1032, and it served his purpose well. It was one of the highest points in the region and had unobstructed space around it for the broadcast of the station’s signal. Programs originating with WQXR in New York City were transmitted by wire to Alpine and broadcast first under the call letters W2XMN and later, WE2XCC. Today, the station is owned by UA Columbia Cablevision Company of Oakland, New Jersey, and is operated for closed circuit TV transmission. During the Second World War, Armstrong devoted himself to military research and allowed the government to use his patents royalty–free. He received the Medal of Merit for his contributions. After the war, Armstrong turned his attention once more to the promotion of frequency modulation. He saw it grow in popularity as a broadcasting medium as more FM stations went on the air and more FM sets were sold to receive the programs. However, few outside the industry had ever heard of Edwin Howard Armstrong—the man who invented it. Furthermore, manufacturers began to build and sell FM equipment ignoring his patents. Goaded perhaps by the bitter memory of losing his regenerative patent years before, Armstrong became embroiled in twenty–one infringement actions to adjudicate his FM patents. Battling giant corporations with batteries of lawyers used up his resources. Finally, in 1954, ill, disillusioned, and his fortune gone, Armstrong took his own life.

After his death, his widow, Marion, set out to finish what he had started. She continued the lawsuits, sitting in the courtroom each day following the arguments and watching as testimony was given. Her first victory, over RCA in 1954, gave her funds to continue the other suits. In 1967, with the victory over Motorola, she had won all twenty–one and established clearly and decisively that Edwin Howard Armstrong was the inventor of frequency modulation. Today, the Alpine tower stands as a monument to the brilliant man whose inventions touch our lives every day. His contributions are perhaps best summed up by Lawrence Lessing in his biography of Armstrong, Man of High Fidelity (J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and New York, 1956). “The lonely man listening to music in the night, the isolated farmer hearing nightly the news of the world, the airplane pilot guiding his craft safely through the ocean of the sky, the astronaut now in his capsule gathering in the whispers from space, the earthbound emergency crew contending with some mission of mercy or disaster, the army on the move and the man in his armchair, charmed or instructed for an hour by a great play a symphony, a speech, a game of ball—all owe a debt to this man who, in some forty years of high fidelity, fashioned the instruments illimitably extending these powers of human communication.” — Jeanne Hammond EDITOR’S NOTE: The above article was written by Edwin Armstrong’s niece, Miss Jeanne Hammond, who owns the copyright. Miss Hammond’s mother, Ethel [Mrs. Bradley Hammond], was Edwin’s sister and a member of the Yonkers Historical Society. The Hammonds lived at 18 Odell Avenue for many years; Jeanne Hammond attended PS #25 and the Halsted School. This article was made possible by the efforts of editorial team member, Tom Flynn, who corresponded with Miss Hammond.

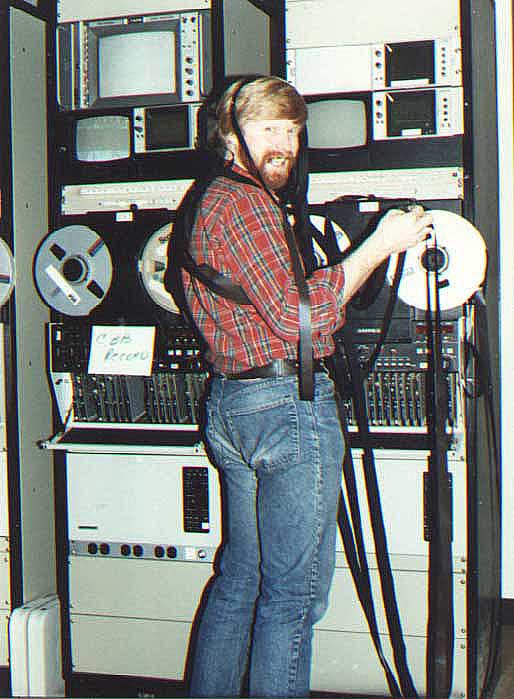

USA Cable Network was located at Armstrong Tower in 1982

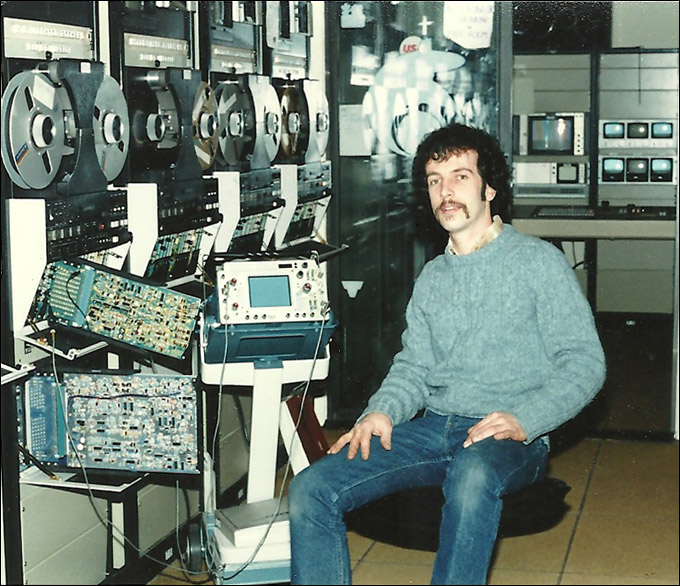

Nework Operations Center

Monte Barry is the Engineer in Charge

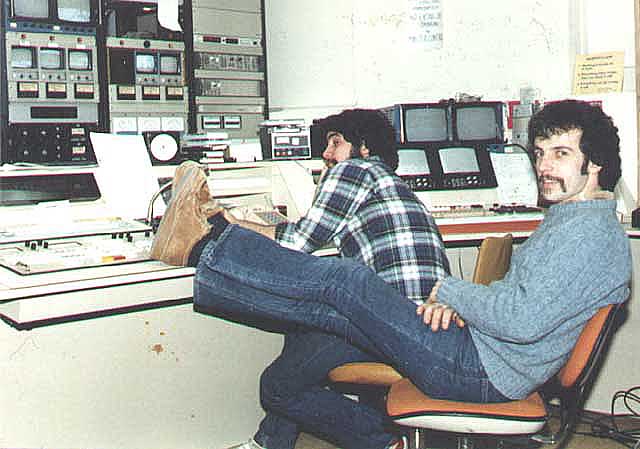

John "JD" Cowles (left) and Terry

we telecast the first NBA games live on USA Network

Seth Berkman and Monte Barry baby-sitting NBA game live-shot

Ampex Video Tape Problem

This post was modified by dead-head_Monte on 2011-01-25 17:58:19

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | Finster! | Date: | Sep 15, 2009 11:31am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead |

many thanks to the Major for all the hours spent in my lifetime listening to music on the radio.

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | johnnyonthespot | Date: | Sep 15, 2009 12:39pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead |

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Sep 5, 2010 10:33am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead |

The boys had a split-feed going off the SBD. This, of course, was common practice (feed A goes to the PA system, feed B goes to the monitors, feed C goes to the Betty Board). The PA feed is getting delayed as it goes through each device. There are equalizers, mixers, limiters, crossovers, amps, and the PA system. Sound boards have effects "send" and "return" feeds. Each device adds a slight time delay to the electronic signal. The total signal delay inside Harding Theatre is more than the signal delay of the raw unequalized audio signal mix being fed to a live shot that is microwaved directly to the radio station's FM transmitter.

There is only one way that a delay like what they describe could be noticed by anyone. You can see it with an audio signal test generator being fed into the system. Then you can measure the time differential on a 2-channel oscilloscope with the 2 different signals from the split-feed. The SBD mix fed to your FM radio was a few hundred microseconds faster than the SBD mix fed to the PA to the crowd. Jerry and Bob were discussing this.

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | johnnyonthespot | Date: | Sep 5, 2010 12:27pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead |

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | laptap3r | Date: | Feb 2, 2011 3:21pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead |

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Feb 5, 2011 9:07am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Edwin H. Armstrong and The Grateful Dead |

This post was modified by dead-head_Monte on 2011-02-05 17:07:08

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11