View Post [edit]

| Poster: | Purple Gel | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 10:56am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

This post was modified by Purple Gel on 2010-07-24 17:56:40

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | AltheaRose | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 12:53pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

I was wondering about the music, actually, because the band would need to sign off on that if the Dead's music were to be used in a movie. I was thinking -- hoping -- that it would just be impossible to get full agreement on that, which could stop the whole thing in its tracks. And you can't exactly do a movie about Jerry with the Dead without the music. Maybe that's one reason they've chosen to focus on his early years ...

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | Jim F | Date: | Jul 25, 2010 12:14am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

As for Garcia and LSD, I don't think it is even possible to underscore the impact it had. In a great Relix article that got passed around back in the Spring, Garcia said "For me it was a profoundly life changing experience. It has a lot to do with where I am now and why I’m here and why I do what I do and it all fits in and it was all happening as I was making the decisions to become who I am, you know what I mean? So it all steered me directly into this place." I think that says it all.

Here is the interview with Jerry, in case you haven't read it. I found it to be a really good read.

http://www.relix.com/features/2010/04/20/q-a-with-jerry-garcia-portrait-of-an-artist-as-a-tripper

Just over 20 years ago, Jerry Garcia sat down to talk candidly about his experience with psychedelics. Save for a few very small excerpts, it’s never before been published. We present the revealing interview, which we published in our August 2008 issue, online for the first time.

I met Jerry Garcia in a hotel room in Buffalo, New York on July 3rd, 1989. Right from the start, he was friendly, warm and open, like we were just a couple of guys chatting over some beers. The room was very plain—no flowers, no paraphernalia, no silver trays with notes from admirers. I can’t say, though, what was in the adjoining room, which I knew was his as well, because at one point the connecting door opened and his girlfriend Menashe walked in. She too, was very friendly, and when I said I would be done soon, she told me not to worry, that she just needed something, but I should stay.

At one point I even mentioned that I had heard he had some Jewish ancestry, but he assured me it wasn’t true. “Well, I’ll skip all the Jewish questions,” I said. “Oh, go ahead,” he chuckled. It was clear that he wanted to talk and maybe that was only partly because of the subject. The rest of it may have been because, well, vegetating in a hotel room before a gig isn’t the most fun. In fact, at one point he just out-and-out said, “Talk as long as you want. I don’t have anything else to do.” It was all very relaxed. I finished up the interview and that was that.

Then about ten years later, I got a call from Dennis McNally, the Dead’s publicist. He was preparing to write A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead and had come across the transcript of the interview that I’d sent him years before. “How did you get this?” he asked. “What do you mean?” I questioned in return. “You’re the one who set it up.” True, he said, but no one else had gotten Jerry to open up that way about his psychedelic experiences, and could he, he wanted to know, use a few quotes in his book. I gave my okay, and then said, “You know, it was funny. It seemed like Jerry wanted me to stay, like he wanted the company, but I was just there as an interviewer, and I couldn’t go beyond my role.” “Tell me about it,” he answered, surprising me, “I felt that way for years.”

In retrospect, I think I know why Jerry was so forthcoming.

When I met him, I was working on a (still unpublished) book about LSD, for which I had already interviewed Albert Hofmann, who discovered it, Timothy Leary, and numerous other people, famous, infamous and unheard of, who had had memorable roles in psychedelic history. I think the project appealed to him, because as he put it, “There are a lot of questions that it would be nice if somebody would address them in a serious way.” I told Jerry a little bit about what I’d learned, the most important point being that the supposed dangers of acid were all hype. He asked me why I was writing about it at all. I told him that LSD had meant a lot to me and I was just being loyal to it. He said he thought that was a good thing. For him, he said, LSD had made it “easier to not fit” into society, and that instead of feeling damaged, as a result, he felt that, “In fact, my life has turned out to be really amazing.” I think Jerry gave me the interview, because, in the end, he was loyal to it, too.

When was the last time you took psychedelics?

Some time in the last year, maybe mushrooms, because I think it’s milder, easier to handle. The nervous system stress is something that a younger body handles better.

You’ve slowed down to what? A couple of times a year?

Yeah, irregularly. It’s not something I plan for. It’s something that I’m likely to do on impulse. But I always keep some psychedelics around. I like to have some DMT. I like DMT ‘cause it takes you a long way and it’s short. It doesn’t take a day and you’re back to reality in like an hour, but in the meantime it sort of blows out the tubes. In terms of the psychedelic requirement—that you experience some kind of supernormal perception of some sort or even imagine that you do, whether it’s in the mind or whatever—if that’s the criterion, then to me there’s times when that’s helpful. It’s like a coffee break almost, you know what I mean?

Does legality make a difference?

To me it does. I don’t think it does in the long run, but it does in the sense of the encroachment of the world at large, the interference of it with the flow of your experience whatever it may be. The modern world I find more frightful, that’s why the high energy mass is a little bit hard to handle, because everything I hear is a siren or a helicopter or something. It’s like immediate paranoia of some sort—sometimes high energy paranoia, full of lots of overlapping horror fantasies and sometimes it’s just interference. And that has to do with something to do with my connotation, that’s my own personal stamp on what the world is like. I don’t feel that it’s a kinder, gentler world.

I’m hoping that people will get a better idea about LSD and psychedelics just from the collective sense of what it really means to people.

For me it was a profoundly life changing experience. It has a lot to do with where I am now and why I’m here and why I do what I do and it all fits in and it was all happening as I was making the decisions to become who I am, you know what I mean? So it all steered me directly into this place.

Were there specific insights? Does it reduce to any kinds of things you can actually talk about?

Well, a couple of like cute one-liners, but basically they don’t translate out here. They have to do with my personality and the voice that’s speaking to me had the same sense of humor. It isn’t like I can’t talk about it. For example, there was one time when I thought that everybody on earth had been evacuated in flying saucers and the only people left were these sort of lifeless automatons that were walking around, and there’s that kind of sound of that hollow mocking laughter, when you realize that you’re the butt of the universe’s big joke. There’s a certain sardonic quality to it that I recognize as my own personality.

You’ve talked about there being a scary side.

For me some of the scary ones were the most memorable. I had one where I thought I died multiple times. It got into this thing of death, kind of the last scene, the last scene of hundreds of lives and thousands of incarnations and insect deaths and these, like, kinds of life where I remember spending some long bout, like eons, as kind of sentient fields of wheat, that kind of stuff. Incredible things and these sort of long, pastoral extraterrestrial kind of cultures, kind of bringing in the sheaves sort of things.

So it was through the dark period and then up again?

Yeah. There was one time that was really memorable, actually it scared me silly but it was also wonderful. One time when I had taken LSD and I think artificial mescaline, and the LSD was “White Lightening” which was incredibly strong and very, very pure. I remember I was lying down on the grass and we were living at the time in a large sort of ranch place in northern California, the band was, and we were all tripping that day, us and a lot of friends. I was lying on the grass and I closed my eyes and I had this sensation of perceiving with my eyes closed—it was as though they were open. I still have this field of vision and the field of vision had a partly visible pattern in it and then I had this thing that outside the field that little thing that you spin around and it takes the little strip of metal off? It was like that and it began stripping around the outside of the field of vision until I had a 360 degree view, and it revealed this pattern and the pattern said “All” in incredible neon. It was, (laughing) it was one of those kinds of experiences. But the fact that these things are happening to you in your own personal language means that they have something to do with whatever it is that’s in your own personal programming. Now a lot of this stuff that I experienced and saw and felt and so forth are things that I don’t think I picked up in this existence. They aren’t directly memories. They aren’t some kind of fusion. They aren’t things I’ve read in books. I don’t know what they were or where they come from. So, there are a lot of questions that would be nice if somebody would address them in a serious way. It’s one of the reasons it’s unfortunate that psychedelics have become confused with drugs.

You have said that the Acid Tests were the best environment for taking acid.

It was for me. A lot of people freaked out though. A lot of people became completely unglued, absolutely. I can’t unqualifiedly say that this was really totally great. My personal experiences were absolutely great.

Why were the acid tests so good for you personally? The freedom?

Yeah, the freedom had a lot to do with it and the synergy—the thing of lots of things happening at once. No specific focus which meant that the kind of pattern beyond randomness, the whole study of chaos has been an interesting kind of affirmation of this sense that when you take away the order something is left. Another level of order comes to the surface. So in that sense the modern study of chaos—fractals and [Benoit] Mandelbrot’s chaos—reflects to me something about the way the Acid Test was when you took the order away from it, the focus away from it and all of the traditional trappings of the division between audience and performer. Say you put a bunch of people in that setting, everything becomes everything, audience and performers are one. The performance and the reality outside the performance are one. And all these things start to happen on other levels and it’s terribly interesting. It’s more than interesting.

What was it like playing the Acid Tests?

It wasn’t one of those things where people paid to come and see us specifically, so we had the option to be able to not play, and there were times when we would play maybe 20 bars and everybody would come unglued and we’d all split. So there were times when we really didn’t want to play, but there were times when we really did want to play, and not only could we play, but since nobody had any expectations about what we were going to play, we could play anything that came into our minds.

Does this have something to do with expectations?

We’ve chosen to go with the thing of we don’t care whether they have expectations or not. We do what we want to do anyway, because what’s in it for us otherwise? We don’t want to be entertainers. We want to play music. That’s what we want to do and we want the music to be interesting for us as performers.

Did you ever have contact with the more scientific side who said you were just wasting your time, destroying yourselves?

People used to say it all the time about the Acid Tests. Too high energy, it’s dangerous, the kind of stodgy, Tim Leary school of the east coast, very cheerful, this is a sacrament.

And what did you say in return?

We said, “Well, who said that we are all doing the same thing? I mean we aren’t researching, we’re partying. We’re having fun.”

A lot of people I’ve interviewed said you get nothing from just partying with LSD.

That was the difference between us and them. For me it was very profound on lots of levels. Going off into the woods and being meditative didn’t cough up anything for me except for how pretty everything is. I got my flashes from seeing other people and interacting with other people, because I was also looking for something in this world not out of it. I was looking for a way to get through this life, not a way to transcend it.

Have your feelings about LSD changed over the years?

They haven’t changed much. My feelings about LSD are mixed. It’s something that I both fear and that I love at the same time. I never take any psychedelic, have a psychedelic experience, without having that feeling of, “I don’t know what’s going to happen.” In that sense, it’s still fundamentally an enigma and a mystery.

What drugs do you do now and how much do you do them including alcohol and nicotine.

I still smoke cigarettes, I don’t drink alcohol very much, once in a while a little bit.

How many cigarettes do you smoke?

I smoke a couple packs a day.

Do you still smoke marijuana?

Once in a while. Not so much as I used to. I sort of stopped. I got into a substance abuse program of my own which went on for quite a long time and then I stopped taking drugs. I quit drugs, I got off them. And I went all the way with drugs. I mean I got into serious hard drugs.

Did you ever put your own physical safety in jeopardy while you were tripping?

Lots of times.

Can you give an example?

Just being without a shirt, that kind of stuff. I mean it’s a thing, you know, what’s your physical safety? Other times I don’t know whether I did or not because I got through it. I went walking in traffic and stuff, but I never thought I was in any kind of danger ‘cause I could see what was coming. I drove a lot of times when I could barely wind my way through the hallucinations. But the fact that I’m here means that I didn’t feel I was risking my life. If I thought I was, I probably wouldn’t have.

Did you ever put anybody else’s physical safety in jeopardy while you were tripping?

I may have, just by being a member of the Grateful Dead. You know, every once in a while there are people who jump off the balcony. They’re leapers and stuff, people who think they can make it happen.

Did you have passengers in your car when you were driving?

I’ve had passengers in the car, but I never once felt that I was risking anybody. I would never risk anybody without risking myself first.

Did you ever make love on acid?

Yeah. It wasn’t for me because one of the things I like about psychedelics was the thing of being liberated from your body. I had a sense of remoteness from my body. Some people, that was their whole trip. But for me it never seemed very appealing. It was too something, too much of the sensorium or something. “Ah, God, it’s too loud,” you know? It wasn’t a very good experience for me.

Should ordinary people be allowed to take LSD?

Why not? I mean, maybe it turns out that there are no such things as ordinary people. Maybe all people are extraordinary.

Did taking LSD change your feelings on death?

Sure. I’m not nearly so afraid of death anymore. I don’t think I was terribly afraid of it before, it never was one of my hang-ups, but I think it really erased anything about fearing it. Psychedelics at their most powerful are scarier than death.

What advice would you give someone contemplating their first trip now?

I’d say go for it. Bring a friend.

Let’s talk about music for a moment. Do you feel some songs are much more psychedelic than others?

No, I don’t. The audience does. There are schools of thought about this, but for me all music is psychedelic. Country and western music is psychedelic. The blues is psychedelic. Everything is psychedelic. All music.

Let’s go back to your first psychedelic experience—peyote. Who gave it to you?

I don’t even remember where I got it from, from a connection that had something to do with the old cabal in Berkeley and there were some people who were members of the Native American church who got it through legitimate channels from the Navahos, Hopis, whatever.

This was before you met Ken Kesey or anything?

Yeah, a long time before that. My friend Bob Hunter had his psychedelics in the federal program at Stanford where Kesey got turned on to it. So I had known about psychedelics and of course I had read The Doors of Perception and saw this show about LSD where they thought at the time that it was producing what they described as a temporary madness, a temporary schizophrenia. I remember being very impressed by this artist who was drawing. He was in this just incredible ecstasy and he was drawing strange things. I thought, “God, I’d love to get some of that,” even when I was a kid.

How was it?

I didn’t get off very good from my first peyote experiences because the taste was so hideously horrible. I got sick as a dog of course and I mean I really wasn’t prepared for it and it wasn’t that great. I mean I had been much weirder before, taking speed for five days and hallucinating madly at the end of it. I already knew that there was something.

Is there any experience that stands out as the highest?

The experience of the dying many deaths. It started to get more and more in kind of a feedback loop, this thing where I was suddenly in the last frames of my life, and then it was like, “Here’s that moment where I die.” I run up the stairs and there’s this demon with a spear who gets me right between the eyes. I run up the stairs there’s a woman with a knife who stabs me in the back. I run up the stairs and there’s this business partner who shoots me. Boom. And it was like playing the last frame of a movie over and over with subtle variations and that branched out into a million deaths of all sorts and descriptions. I don’t think I ever really recovered from it.

Well what does that mean? You mean you were transformed by it?

Yeah, I was a different person then again.

Well what do you make of reality now?

I think it’s mostly a joke pretty much. It’s hard to take it very seriously just because I know that just around the corner, metaphorically speaking, there’s a whole lot more. There’s a whole lot of other stuff. I don’t know what it is or why it’s there or why it’s so highly organized, but I know that this reality is basically tossing cards in a hat. In the face of all of the stuff there is in the mind.

Why shouldn’t LSD be considered as just another drug?

My feeling about it is that all drugs should be legal. I think heroin should be legal. I think that cocaine should be legal. I don’t mean legal exactly. If they want to take the narco dollar out of existence. If they want to make it so that that huge sum of money that people are spending that the economy is going, it’s leaving this country, the way to do it is to make it so that people pay what they’re actually the cost of. I mean, drugs are not expensive.

The thing is that you say it’s different. We all feel it’s different. But what is the difference?

I think the difference is that LSD is not strictly pleasurable. I think that you could take cocaine and pretty much never scare yourself or heroin for that matter. Apart from having an overdose and being uncomfortable for a while—say, for cocaine or dying with heroin—but you certainly die peacefully. LSD can scare you and that’s one of the things that makes it different.

The last thing I want to ask you about, this is sort of an odd question but it’s a simple one: Why are you giving me this interview?

I want to be able to say to people in this time, with the big “Just Say No” where everybody is so roundly against drugs, that, hey, not all drug experiences are negative. I would like for that minority voice to be heard. Some drug experiences are quite positive and can be life-enhancing and can be pleasant and can be not dangerous and don’t necessarily promote criminal activity.

One of the quotes that I read was that you realized there was more than we’d been allowed to believe.

Yeah.

Who allows us?

That’s what I wonder. Who is the guy, where does it say, even in the ten commandments, “Thou shalt not get high. Thou shalt not change your consciousness”? Who says? The way I understood it, it was helpful to change your consciousness sometimes.

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | AshesRising | Date: | Jul 25, 2010 3:37am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

"Let the world go by, all lost in dreaming,"

--- AshesRising

Reply [edit]

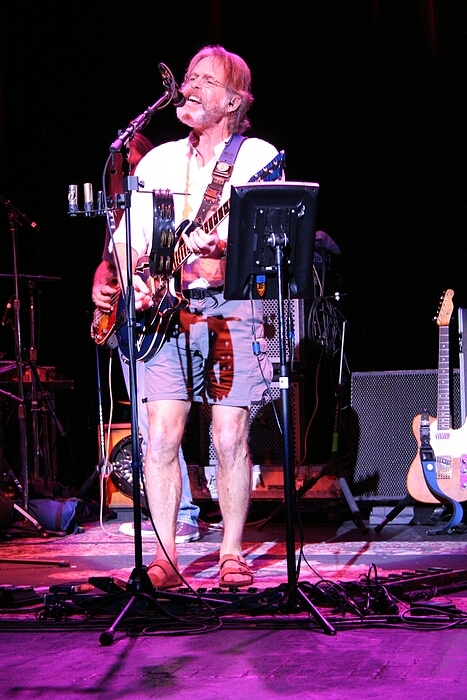

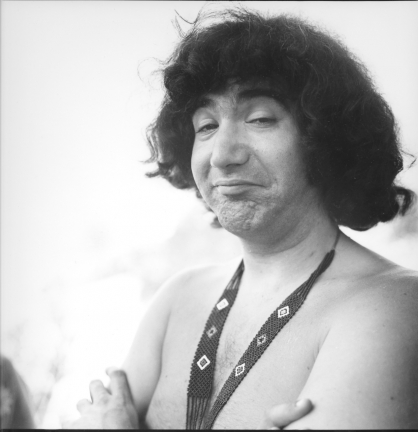

| Poster: | Street Pig ! | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 11:07am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

This post was modified by Street Pig ! on 2010-07-24 18:07:05

Attachment: 1970_jerysidehollywood.jpg

Attachment: 1970_deadhollywood3guitars.jpg

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | skuzzlebutt | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 11:21am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | Lou Davenport | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 12:00pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | Reade | Date: | Jul 25, 2010 10:49am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | 'Heart Beat' anyone? |

For starters it would have to prominently depict the beatnik era, I should think, and that never seems to go well. Heart Beat, a 1980 film starring a young Nick Nolte and Sissy Spacek as Neal and Carolyn Cassady comes to mind, along with the Maynard G. Krebs guy on Dobie Gillis.

Depictions often don't succeed at transcending the physical props- the berets, the goatees, sunglasses, black coffee, etc. Delving into the social forces of a culture responding to living with the atomic bomb for the first time, the more hollow aspects of post war prosperity and conformity, etc. apparently is just .....too difficult or something.

Plus after watching Weir in that Hell In A Bucket video I don't think i'm anxious to see him or even an actor playing him on the big screen anytime soon.

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Jul 25, 2010 1:27pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: 'Garcia's Island' anyone? |

— beatnicks playing bass with Jer —

Jer and Robert Hunter

Phil and Jer

starring Robin Williams as Uncle Bob

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 1:06pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

This source is Jerry Garcia - from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia this is the Relocation and band beginnings section Garcia stole his mother's car in 1960, and as punishment, joined the United States Army. He received basic training at Fort Ord. After training, he was transferred to Fort Winfield Scott in the Presidio of San Francisco. Garcia spent most of his time in the army at his leisure, missing roll call and accruing many counts of AWOL. As a result, Garcia was given a general discharge on December 14, 1960. After his discharge in January 1961, Garcia drove down to East Palo Alto to see Laird Grant, an old friend from middle school. Garcia, using his final paycheck from the army, purchased some gasoline and an old Chevrolet car, which barely made it to Grant's residence before it broke down. Garcia proceeded to spend the next few weeks sleeping where friends would allow, eventually using his car as a home. Through Grant, Garcia met Dave McQueen in February, who, after hearing Garcia perform some blues, acquainted him with many people from the local area, as well as introduced him to the people at the Chateau, a rooming house located near Stanford University which was then a popular hangout. On February 20, 1961, Garcia entered a car with Paul Speegle, a 16-year-old artist and acquaintance of Garcia; Lee Adams, the house manager of the Chateau and driver of the car; and Alan Trist, a companion of theirs. After speeding past the Menlo Park Veterans Hospital, the car encountered a curve and, traveling around ninety miles per hour, collided with the traffic bars, sending the car rolling turbulently. Garcia was discharged through the windshield of the car into a nearby field with such force he was literally thrown out of his shoes and would later be unable to recall the ejection. Lee Adams, the driver, and Alan Trist, who was seated in the back, were thrown from the car as well, suffering from abdominal injuries and a spine fracture, respectively. Garcia escaped with a broken collarbone, while Speegle, still in the car, was fatally injured. The accident served as an awakening for Garcia, who later commented: "(t)hat's where my life began. Before then I was always living at less than capacity. I was idling. That was the slingshot for the rest of my life. It was like a second chance. Then I got serious". It was at this time that Garcia began to realize that he needed to begin playing the guitar in earnest—a move which meant giving up his love of drawing and painting. Garcia met Robert Hunter in April 1960. Hunter would go on to become a long-time lyrical collaborator with the Grateful Dead. Living out of his car next to Robert Hunter on a lot in East Palo Alto, Garcia and Hunter began to participate in the local art and music scenes, sometimes playing at Kepler's Books. Garcia performed his first concert with Hunter, each earning five dollars. Garcia and Hunter would also play in a band with David Nelson, a contributor to a few Grateful Dead albums, labeled the Wildwood Boys. In 1962 Garcia met Phil Lesh, the eventual bassist of the Grateful Dead, during a party in Palo Alto's bohemian Perry Lane neighborhood (where Ken Kesey lived). Lesh would later write in his autobiography that Garcia resembled the "composer Claude Debussy: dark, curly hair, goatee, Impressionist eyes". While attending another party in Palo Alto, Lesh approached Garcia to suggest that he record some songs on Lesh's tape recorder (Phil was musically trained, though he did not start playing bass guitar until the formation of the Grateful Dead in 1965) with the intention of getting them played on the radio station KPFA. Using an old Wollensak tape recorder, they recorded "Matty Groves" and "The Long Black Veil", among several other tunes. Their efforts were not in vain, and they later landed a spot on the show, where a ninety-minute special was done specifically on Garcia. It was broadcast under the title "'The Long Black Veil' and Other Ballads: An Evening with Jerry Garcia". Garcia soon began playing and teaching acoustic guitar and banjo during this time. One of Garcia's students was Bob Matthews, who later engineered many of the Grateful Dead's albums. Matthews went to high school and was friends with Bob Weir, and on New Year's Eve 1963, he introduced Weir and Garcia to each other. Between 1962 and 1964, Garcia sang and performed mainly bluegrass, old-time and folk music. One of the bands Garcia was known to perform with was the Sleepy Hollow Hog Stompers, a bluegrass act. The group consisted of Jerry Garcia on guitar, banjo, vocals, and harmonica, Marshall Leicester on banjo, guitar, and vocals, and Dick Arnold on fiddle and vocals. Soon thereafter, Garcia joined a local bluegrass and folk band called Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions, whose membership also included Ron "Pigpen" McKernan. Around this time, the psychedelic LSD was beginning to gain prominence. Garcia first began experimenting with LSD in 1964; later, when asked how it changed his life, he remarked: "Well, it changed everything [...] the effect was that it freed me because I suddenly realized that my little attempt at having a straight life and doing that was really a fiction and just wasn't going to work out. Luckily I wasn't far enough into it for it to be shattering or anything; it was like a realization that just made me feel immensely relieved". In 1965, Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions evolved into the Warlocks, with the addition of Phil Lesh on bass guitar and Bill Kreutzmann on percussion. However, the band quickly learned that another group was already performing under their newly selected name, prompting another name change. After several suggestions, Garcia came up with the name by opening a Funk and Wagnall's dictionary. He was then promptly greeted with the "Grateful Dead". The definition provided for "Grateful Dead" was "a dead person, or his angel, showing gratitude to someone who, as an act of charity, arranged their burial". The band's immediate reaction was disapproval. Garcia later explained the group's feelings towards the name: "I didn't like it really, I just found it to be really powerful. [Bob] Weir didn't like it, [Bill] Kreutzmann didn't like it and nobody really wanted to hear about it. [...]" Despite their dislike of the name, it quickly spread by word of mouth, and soon became their official title.

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | Purple Gel | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 1:15pm |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | johnnyonthespot | Date: | Jul 24, 2010 10:47am |

| Forum: | GratefulDead | Subject: | Re: Jerry Bio-pic (reprise) |

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11