View Post [edit]

| Poster: | internet rising | Date: | Jan 15, 2012 1:48am |

| Forum: | occupywallstreet | Subject: | #!? review for a new documentary film "INTERNET RISING" |

This post was modified by internet rising on 2012-01-15 09:48:20

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Jan 15, 2012 3:06pm |

| Forum: | occupywallstreet | Subject: | Re: #!? review for a new documentary film 'INTERNET RISING' |

This is an excellent documentary. It's Reality Check 101! "It's all connected." Thank you for posting this here. Welcome aboard! This film presents an excellent conversation we all need to be having in the U.S.A. right now. If the DNS servers are attacked, or if they go down, it's over. "We can take down the Internet in thirty minutes!" says the filmmakers. (The root Internet servers, only 13 centralized super-computers, are The Entire World's domain name look-up table for The Internet. This connects web site names to IP addresses and web servers. Internet connections and TCP/IP data packets bring the internet and the world wide web to your device's Internet Browser. This is the way The Internet works as I understand it.) Here's additional review and disussion content for the film's documentary about The Internet: • Ex-FCC Commissioner Michael Copps interview on Democracy Now - Jan 12, 2012

Media Consolidation, Broadband Expansion, Threats to Journalism - some excerpts• Net Neutrality discussion thread Media Ownership and Consolidation is discussed

Amy Goodman, intro: Michael Copps served two terms with the Federal Communications Commission. Now the staunch supporter of an open internet and opponent of media consolidation has retired. In a wide-ranging discussion, he examines the FCC’s key accomplishments and failures of the past decade. Copps argues broadband is "the most opportunity-creating technology perhaps in the history of humankind," and laments that the United States still lacks a national broadband infrastructure. He says the FCC has yet to address a lack of diversity in media ownership, noting that "owning a station has a lot to do with the kind of programing that’s going to be on that station." Regarding the future of journalism, Copps calls on the FCC to make access to quality journalism a "national priority," saying, "the future of our democracy hinges upon having an informed electorate." Michael Copps: I have a passion on media issues. I’m extremely worried about the future of our media, because I think it impinges so directly on the future of our democracy and the future of self-government. And I think, between the private sector and the public sector, we have wreaked untold havoc on the media environment, and I hope we can have an opportunity to talk about that this morning. None of this de-emphasizes the excessive clout that big corporations and big money wield in Washington right now. I’m saying we’re doing a little bit better, but we’ve still got a long, long way to go. Juan Gonzalez: Well, Commissioner Copps, on the issue of universal broadband policy, why is it that this country has fallen behind, when it comes to — compared to many other countries in the world, in terms of citizen access not only to broadband, but to high-speed broadband? Michael Copps: We forgot how we built America. We always, when we built infrastructure in the past, had the public sector and the private sector working together. The private sector is the lead economic engine pulling the locomotive, but heading toward a vision, heading toward a national goal, when we were building those railroads and becoming a continental power and building the interstate highway system. And then we got off on this tangent, beginning in the '80s, that the market would solve all of these problems. You didn't need government, you didn’t need a vision. So, we went from being first or second in broadband in 2001, when I joined the Federal Communications Commission, to now 15th, 20th, 24th. I don’t know precisely where. It depends on whose ratings you read. But I know, wherever we are, it’s down there where your country and mine should never be finding itself. Amy Goodman: What about that — Michael Copps: So you have to have a strategy. We didn’t have — we didn’t have the strategy, and a sense of mission, even now, although the Commission has reformed universal service, which is the system that subsidized telephones for rural areas and low-income areas. We’ve got to see this not as a problem that jiggering with the universal service system can resolve. This has to be a national vision. Somebody has to say, this stuff is really important to the future of the United States of America, if we’re going to create jobs, become competitive in the world economy, create opportunity for all of our citizens. Amy Goodman: What about that? I don’t know if people in the United States understand the level to which, in countries throughout Europe and in Asia, as well, there is universal access to broadband. Michael Copps: Right. Amy Goodman: It’s sort of like being able to go to a public school. But in this country, the large swaths of the country that don’t have access to this, that it’s a wholly issue of private enterprise and who can afford to get online. Michael Copps: Right. Well, it’s a two-pronged problem. It’s a question of deployment and getting the connections out there — wireline, wireless, fiber, what it is. And also it’s a question of adoption. People need to understand how important this is. I am a strong proponent that one of our national priorities needs to be digital or media or news literacy, call it whatever you want, educating all of us, particularly the young children. I’d like to see a K-through-12 digital literacy, media literacy program, where you teach folks not only how to use this stuff for their own advancement, but also what to look out for and what to trust and what’s a trustworthy news site, what’s a reliable one, what’s news, what’s opinion, what’s fact, what’s rumor. So, media literacy is high on the list of our national needs, so people can really understand how important this is. If they’re going to find a job, you don’t find a job anymore by stuffing your résumé in an envelope and sending it off to a Fortune 500 company. They won’t even look at it. They hire only online, when they hire. Juan Gonzalez: Well, Commissioner Copps, I’d like to ask you about another aspect of this same broadband issue, which is wireless. One of the last decisions or cases that you were involved with was the T-Mobile, AT&T — the AT&T’s attempt to merge with T-Mobile. And the increasing importance of wireless smartphones in terms of how people get their information and their data, and the issue of whether internet freedom, or what people call net neutrality, will be preserved in wireless communications? Michael Copps: Well, I certainly hope so. That was one of the shortfalls when the Commission addressed network neutrality, that the majority concluded that it was a different technology and was not ready to have those rules applied to it. I disagree strongly with that. Every day, thousands and thousands of people are disconnecting the land line and going wireless. A huge part of the future of the broadband internet is going to be wireless. So we need — you know, we need to be technology neutral. We need to be working with fiber where fiber is appropriate, with wireline, with satellite in those places where it is. But we need to realize that you have to have rules of the road. And I think wireless is far enough along where it should be expected to be open access, internet freedom. Otherwise, we’ll have the wireless network build out, and it will be exempt from all these rules, and you’ll end up with tollbooths and gatekeepers, and you will have badly beaten down the whole historic potential of the internet to improve our lives. Juan Gonzalez: Commissioner Copps, you not only were a long-serving commissioner, but many reform advocates consider you the — perhaps the most progressive commissioner in the history of the agency, certainly dating back to the days of Nicholas Johnson, but probably, in terms of your impact, even more so, specifically because of your efforts in the earlier part of the last decade to get the public directly involved in media policy. When Chairman Michael Powell, President Bush’s first chairman, attempted to the deregulate ownership rules, you took an extraordinary step of going out across the United States, holding informal public hearings to hear what the American people felt about their media system and how ownership should be regulated. Could you talk a little bit about your decision to do that and the impact that that had in getting citizens involved in media policy? Michael Copps: Well, it’s interesting, Juan. When I first arrived at the FCC in 2001, and I think the then-chairman was already considering loosening our media ownership rules so that fewer and fewer mega media companies could gobble up more and more independent family-owned media outlets, and I think the majority probably thought this is pretty much of an inside-the-Beltway game, nobody is interested in numbers of outlets anybody can own outside the Beltway, so we’ll just do it here. And my colleague, Jonathan Adelstein, and I believed otherwise. And we took to the road, attended a lot of hearings. Probably, in the years I was at the FCC, I went to 75 or so hearings held by members of Congress, advocacy groups, consumer groups, a few by the Commission, not nearly enough. And back at that particular time that your reference, we just saw across the nation a tremendous amount of interest and an appreciation for the fact that something had been lost in media, a realization that all of this consolidation that we had been through had led to closing of newsrooms, firing of reporters. Right now we’ve got thousands and thousands of reporters who are walking the streets in search of a job, and they should be walking the beats in search of a story. The American people are not being properly informed. But anyhow, back to the point. After the first year of those hearings and all of these consumer and advocacy groups working so hard, more than three million Americans — more than three million — contacted the FCC and the Congress, said, "We don’t want any part of these rules. Don’t pass these rules." They had already been rammed through the Commission, but because of this public reaction, the Senate voted to overturn them, the House voted against them, and then the Third Circuit Court in Philadelphia sent them back. But we’re still diddling around with those rules here, almost 10 years later. We haven’t tightened the rules. We haven’t done anything about media consolidation. And the situation gets worse and worse, and the consolidation goes on and on. And so people say, "Oh, well, it’s all over with." Not so. We had NBC Universal-Comcast earlier this year, Sinclair buying up a bunch of stations, Cumulus and Citadel. And I think when the economy turns a little bit, you’re going to see a lot more of this consolidation. And every time you consolidate, you lose a local voice, you lose an element of localism, you lose coverage of the — of a community’s ethnic diversity and its cultural diversity. And it’s bad for America. Amy Goodman: On the issue of regulation and monopolies, Commissioner Copps, you were the only commissioner to vote against the Universal-Comcast merger. Explain the significance of what this merger is all about. Michael Copps: Well, it’s just a question of too much power in too few. And this was a merger that was not only old media, but new media, too, and the internet and broadband. And one thing we have to really be careful of in this country—we know what’s happened as a result of consolidation in radio and television and cable. Now we have this awesome new technology of broadband and the internet. Are we going to allow it to go down that same road, denying its historical potential, and let it become the province of gatekeepers and controlled by a few? You know, I’ve spent 10 years at the Commission, and it’s all — it’s just, every day, one company comes in. "We want to get bigger." And the majority, many times over the past years, has said, "Fine." They approve that. So then the competitor comes in and says, "We’ve got to get bigger." And it’s just do this day after day after day, while the consolidation continues, and localism and diversity and competition suffer, and the American people suffer with it. Juan Gonzalez: Commissioner, I wanted to ask you about the whole issue of journalism and the future of journalism. You’ve often expressed your concerns about this. The reality is that the advertiser-driven model of the old media, which basically sustained the salaries of reporters in newspapers and television stations, is fading away. The new media, there’s lots of people working in new media, but they’re not getting paid decent salaries to maintain families and buy homes. What should be the role of government in, somehow or other, assuring — and how could it assure — that local news is produced by people who work at these jobs on a full-time basis and can afford to maintain families doing that work? Michael Copps: Well, you’ve put your finger on, I think, maybe the biggest problem that the country faces right now, and that’s what’s happened to media journalism. Most of the news that we get in the United States of America, 90 to 95 percent of it, still comes from the newspaper newsroom and the broadcast television newsroom. It’s not coming from blogs or the internet. There are wonderful, interesting and innovative experiments out there, but this is the reality. The problem is, there is so much less of that news, because of the developments in the private sector that we talked about with consolidation and because of the abdication of its public interest responsibilities by the FCC over the last 30 years in not insisting on some public interest guidelines and enough news. I got so impassioned about this problem, because I think the future of our self-government, the future of our democracy, hinges upon having an informed electorate, an electorate with sufficient depth and breadth of information that they can make sense out of all of the complex problems that we face and make intelligent decisions for the future of the country. And goodness knows, we face some of the most awesome challenges right now in terms of our economy coming back, our global competitiveness being able to return, creating opportunity, health — you know, the whole list. But all of those issues are going to depend upon decisions made by the people, and those have to be fact-based. And you can’t have a situation where we’re saying, "Well, yeah, it’s too bad what happened to newspapers and broadcast, but the new media is going to fix that," because we don’t have a model there for that. I guess maybe the first thing we need to do is just stop thinking about old media and new media and just think about: we have a media environment right now in front of us. Part of it’s traditional, but it’s all one thing. This is how we inform ourselves. This is our information infrastructure. What are we going to do about it now? We can’t sit around and wait. We can’t watch journalism hemorrhage. We can’t watch investigative journalism go down the tubes. So this has to become really a national priority. There are down payments. There are things we can do right now, that the FCC could do tomorrow morning. For instance, in the world of broadcasting, you know, we used to have some guidelines, public interest guidelines, that we would look at when a broadcaster came in to renew his or her license every three years. Well, all of that’s gone now, beginning in 1980. We had — '81, we had an FCC chairman who said, you know, a television set is nothing but a toaster with pictures. And that's how they went on to conduct their public interest oversight. They got rid of all the public interest guidelines. The license period went from three to eight years. Now you send in a postcard, and basically, no questions asked, you get it back. I’m not saying that having some public interest guidelines is going to solve our media problem, but it would be a down payment. And it would have immediate effects in broadcast. It would have some spillover effects in newspapers, because so many newspapers and broadcast stations are owned together. And it would get — it would get a dialogue going and confront this problem of what is the public interest on the internet. We have to have a discussion in the United States of America if we’re going to move the town square of democracy to the internet and pave it with broadband bricks. How are we going to assure that it’s accessible to all, open to all, and not only can you type something and send it into the ether, but that you’re going to be heard, that you have some access to the conversation? That’s public interest. And there is public interest consideration on what the future of the internet is going to look like. There is a role, and we need to have a calm, cool, rational discussion about this very, very soon, or we’re going to lose the opportunity, really, to craft a media future that’s worthy of the country. And this goes back in history. The builders of this country have always been interested in creating information infrastructure. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison were presiding over this new experiment in democracy. And they knew that it hinged, this experiment, on an informed electorate. So they made sure — the writers of the First Amendment, they made sure that we had newspapers getting out to every American. They built post roads. The subsidized newspaper rates so that the news could get out. And that’s — that’s the kind of challenge we have to look at now. Our challenge in this century is the very same thing. The technologies change. Names change. The democratic — the small "d" democratic — challenge remains the same: make sure that electorate is informed, if you wish to sustain self-government. • Ex-FCC Commissioner Michael Copps entire interview on Democracy Now, Jan 12, 2012

Our Internet is 100 per-cent occupied by the One per-cent! (That's what They think!)

• Outsourcing U.S. Manufacturing and Electronics Jobs • Jan 12, 2012 - "Internet workers" in China threaten mass-suicide over Foxconn's reassignments. In this case, Foxconn is the maker of parts for Microsoft Corp.’s Xbox. For years, The Taiwan-based Foxconn Technology Group's internet slave-labor workforce, over one million people in China and growing, has been used by Microsoft, Apple, HP, Dell, IBM, Sony, Nokia, and the One Per-Cent! These slaves are working in electronics factories in China. It's disgusting to me what these corporations are doing to these People! The 99 Per-cent need to know about all of this.

Foxconn Technology Group's electronics workers are internet workers! They are electronics workers making internet devices! They are earning $250 per month for working 15 hours per day, six days per week, under extremely brutal working conditions! Suicides are prevalent amongst Foxconn workers. At least 18 of them have leaped to their deaths, committing suicide on the job. Dangerous working conditions caused several of them to get killed on May 20, 2011 in an explosion. Three internet workers died that day on the job for Foxconn in Chengdu, China - killed in the explosion on Apple's i-Pad2 production line. This has been thoroughly investigated, documented, and ignored! Foxconn Technology Group's slave workers are The People manufacturing most of the internet devices we are using! Why do the filmmakers mention nothing about these facts? I am a former live music taper and soundman. I am a retired broadcast engineer. I have over thirty years experience working professionally in electronics on pro-video and pro-audio systems for Manufacturers, TV Broadcasters, Cable TV systems, Cable TV Networks, Newschannels, News Departments, and Network Operations Centers. Morality and Moral Creatures get discussed and connected to The Internet in the film at 38:00. The Facts I've provided about the Foxconn Technology Group are never mentioned in the Internet Film. Where do our internet devices come from? Imo, not asking this question when making this film is immoral, given The Facts of The Matter at Hand! I'm ashamed of myself, so I've published this document for The Archive, and for the filmmakers. Please pass this information along to everyone on The Internet, and everyone in the OWS Movement. Thank You very much. The meta-system here in America is called the United States of Amnesia! re: my review for the the Internet Rising documentary film. I'm submitting it to you. I give it 3½ stars. It's a great film. Thank you for posting here!

Reviewer: dead-head_Monte

MonteVideo GrafixI'm interfacing peacefully with The OWS Network

• Tapers, taping OWS, and The Taper's Compendium Project where does the Live Music Archive come from?

broadcasting from Fort Collins

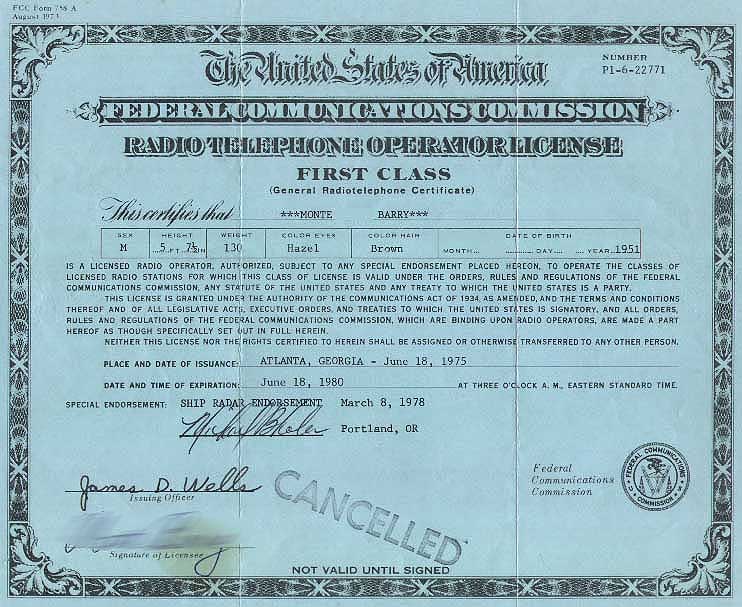

• current FCC Radiotelephone Operator License for Monte Barry

• original FCC Radiotelephone Operator License for Monte Barry - front

• original FCC Radiotelephone Operator License for Monte Barry - back

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Jan 26, 2012 7:32am |

| Forum: | occupywallstreet | Subject: | Re: #!? review for a new documentary film 'INTERNET RISING' |

The iEconomy

In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an iPad

By CHARLES DUHIGG and DAVID BARBOZA Gu Huini contributed research. Published: January 25, 2012 (below are a few paragraphs from page 1) The explosion ripped through Building A5 on a Friday evening on May 20, 2011. An eruption of fire and noise twisted metal pipes as if they were discarded straws. When workers in the cafeteria ran outside, they saw black smoke pouring from shattered windows. It came from the area where employees polished thousands of iPad cases a day. Two people were killed immediately, and over a dozen others hurt. As the injured were rushed into ambulances, one in particular stood out. His features had been smeared by the blast, scrubbed by heat and violence until a mat of red and black had replaced his mouth and nose.

In the last decade, Apple has become one of the mightiest, richest and most successful companies in the world, in part by mastering global manufacturing. Apple and its high-technology peers — as well as dozens of other American industries — have achieved a pace of innovation nearly unmatched in modern history. However, the workers assembling iPhones, iPads and other devices often labor in harsh conditions, according to employees inside those plants, worker advocates and documents published by companies themselves. Problems are as varied as onerous work environments and serious — sometimes deadly — safety problems. Employees work excessive overtime, in some cases seven days a week, and live in crowded dorms. Some say they stand so long that their legs swell until they can hardly walk. Under-age workers have helped build Apple’s products, and the company’s suppliers have improperly disposed of hazardous waste and falsified records, according to company reports and advocacy groups that, within China, are often considered reliable, independent monitors. More troubling, the groups say, is some suppliers’ disregard for workers’ health. Two years ago, 137 workers at an Apple supplier in eastern China were injured after they were ordered to use a poisonous chemical to clean iPhone screens. Within seven months last year, two explosions at iPad factories, including in Chengdu, killed four people and injured 77. Before those blasts, Apple had been alerted to hazardous conditions inside the Chengdu plant, according to a Chinese group that published that warning. “If Apple was warned, and didn’t act, that’s reprehensible,” said Nicholas Ashford, a former chairman of the National Advisory Committee on Occupational Safety and Health, a group that advises the United States Labor Department. “But what’s morally repugnant in one country is accepted business practices in another, and companies take advantage of that.” Apple is not the only electronics company doing business within a troubling supply system. Bleak working conditions have been documented at factories manufacturing products for Dell, Hewlett-Packard, I.B.M., Lenovo, Motorola, Nokia, Sony, Toshiba and others. Apple was provided with extensive summaries of this article, but the company declined to comment. The reporting is based on interviews with more than three dozen current or former employees and contractors, including a half-dozen current or former executives with firsthand knowledge of Apple’s supplier responsibility group, as well as others within the technology industry.

I, Monte Barry, am 60 years old. I taped the Grateful Dead numerous times in 1973, beginning on June 9 and 10, at RFK Stadium. The Grateful Dead used Ampex audio tape decks dozens of times to record their SBDs, albums, and other commercial releases. I also taped many other bands in the mid-1970s. I worked 3 years as a soundman through 1976. Then I worked for Ampex for 6 years, beginning in 1979. Ampex invented the videotape recorder in 1955. Awards for Technical Excellence issued to Ampex for products and technology Ampex developed during the period 1957 - 1990 include eleven Emmy Awards, a Grammy Award, and an Oscar. Alembic developed and produced much of the equipment that was used by the Grateful Dead for their famous "wall of sound" PA System in 1973 and 1974. Ron Wickersham, one of Alembic's founders, worked previously as an audio engineer for Ampex. Alembic is best known for making fine modern guitars and basses. I've worked over 30 years in electronics. Ampex never had any explosions in their main Audio-Video Systems Division factory in Colorado Springs. Ampex workers were not getting killed there on the job. This plant operated in Colorado for many years during the '70s, '80s, and '90s. I worked there for 3 years; and 3 years Ampex field service engineer in the NYC area. Ampex workers were not severely stressed out and subjected to harsh working conditions. In fact, no Ampex workers ever committed suicide due to these reasons. Ampex technicians and engineers were and are very highly regarded by Broadcasters, Cable TV Networks, NAB, SMPTE, AES, and other professional organizations. Ampex technicians and engineers were and are among the highest sought-after, and highest-paid, workers in Broadcasting. I epitomize this fact. Alembic never had any explosions in their main facility. Alembic workers are not getting killed there on the job, nor have I ever heard of any of them committing suicide due to being subjected to harsh working conditions.

Reply [edit]

| Poster: | dead-head_Monte | Date: | Feb 10, 2012 11:41am |

| Forum: | occupywallstreet | Subject: | Re: #!? review for a new documentary film 'INTERNET RISING' |

• Apple, Accustomed to Profits and Praise, Faces Outcry for Labor Practices at Chinese Factories Charles Duhigg and Mike Daisey were interviewed on the Democracynow newshour program today, on the War and Peace Report. Charles Duhigg is an award-winning staff reporter for the New York Times. He helped break this story about the human costs of Apple products for workers in China. Mike Daisey is a Playwright and actor who is currently performing a one-man show called, "The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs." He has visited factories in China that make Apple products and interviewed the workers. I copied a few excerpts and assembled them below...

AMY GOODMAN: You went to China. MIKE DAISEY: Yes. AMY GOODMAN: You talked to these workers. Describe the breadth of the place and what you found when you talked to these workers. MIKE DAISEY: Well, I think this conversation is fantastic. I think that it does feel like we’re in a post-industrial society, so this place is all the engines we need to run everything we make. The scale is really staggering. You’re talking about rooms that hold 20,000, 25,000, 30,000 workers, in enormous rooms where people work silently. I think one of the things we don’t think about a lot is that — when things are made by hand. When the cost of labor is unbelievably cheap, the most effective way to exploit that is to assemble by hand. So, despite the fact that our devices are so advanced, once the parts of that device are made, they’re assembled by hand. So these things that seem so advanced — and are so advanced — the supply chain that’s evolved has a component in it that involves many, many small hands putting your devices together in a row, one after another, despite the fact that your Apple product looks so pristine. In fact, one of the last steps is to put a sticker over it that makes it look as though no human has ever touched your Apple product. JUAN GONZALEZ: The reason why so many American factories left the United States — as the industrial workers became unionized, they were able to increase the pay and better their working conditions. What — when you started talking to the Chinese workers there, what about the labor unions? What about the ability of the workers to organize in these huge plants? Why has that not occurred at a more rapid and a more developed pace? MIKE DAISEY: Well, I mean, there’s a really simple explanation. Labor organization in China is illegal. If you organize a union in China that is separate from the Communist Party, and those are largely fronts, in terms of working conditions, you go to prison if you’re caught by the government. So, that largely shuts down any sort of serious effort at labor organization. I think that’s part and parcel of the landscape. I mean, there’s a reason why this environment works so well for the needs of creating a hyperinflated, hyper-growing industrial revolution, and that’s that you have a base of workers who live under an authoritarian government and can be controlled. The circumstances are very controlled. And so, I think that’s part of the equation that we don’t like to look at. AMY GOODMAN: How the company deals with the suicides, and what actually is happening? What are Chinese workers doing? MIKE DAISEY: Well, there was a series of suicides at Foxconn where, month after month, workers would go up to the roofs of the buildings and throw themselves off the buildings, in a very public manner. The thing about this is that the number of suicides is not the issue so much as the cluster. The fact that people were choosing to kill themselves in an incredibly public manner is really relevant and has to do, I think, with pressures of the production line. It’s a very intense environment. And the people who come into those jobs are often in a very blessed position. They’ve come from the rural areas, and they’re making a new life for themselves. But they have to send money back to many, many dependents back where they come from. So they’re in a perfect position to be exploited, like they don’t feel, in some cases, like they can leave. And it can be very tough. AMY GOODMAN: And how the company dealt with the suicides? MIKE DAISEY: Well, Foxconn chose to deal with the suicides, in the period when I was visiting — what they had done, after month after month of suicides, was put up [safety] nets. AMY GOODMAN: [safety] Nets? MIKE DAISEY: Yes. AMY GOODMAN: To catch the bodies. JUAN GONZALEZ: I wanted to ask Charles Duhigg about Foxconn, because one of the abilities of American companies now is to have these foreign suppliers, so that they have this wall, supposedly, between their own employees and employment conditions and these contractors. Who is Foxconn? Who owns it? How did it arise? And what is its importance today in China? CHARLES DUHIGG: Foxconn is hugely important not only in China — it’s the largest employer in China — Foxconn is important around the world. So, Foxconn — and in some ways, it’s a remarkable story. It started — it’s owned by a Taiwanese gentleman named Terry Gou, who started in Taiwan rebuilding circuit boards in, essentially, a — one little sort of storefront with a couple of other people, very, very low-level labor. And he’s built that now into the largest electronics manufacturer in the world. Forty percent of all electronics sold are assembled by Foxconn. He employs about 1.2 million people in China, so he’s among the largest employers. And more importantly, the psychological impact of Foxconn is tremendous throughout Asia, because, as Terry Gou has become one of the richest people in the world, he’s shown that there is this path towards enormous wealth creation by taking very, very simple tasks, automating them with humans, and then going and competing for contracts. And so, one person I talked to, who was a former Apple employee, had told me that basically Apple helped make Foxconn real. You know, they were a large supporter of the company, and have been for many years, because they need Foxconn. Without Foxconn — and there’s only really one or two other companies that can do what Foxconn does — you can’t produce 300 million iPhones. You need a partner like this that you can give designs to, and they can start it rolling out a week later. And Foxconn does it amazingly. Now, conditions inside the plants are fairly harsh, as Mike so eloquently describes. But it is — it’s a new type of company that really we haven’t seen in history. AMY GOODMAN: Talk about this worker ["the man with the claw"]. MIKE DAISEY: This is a worker I spoke with whose hand had been maimed in a metal press. And he said he had not received any medical treatment, and his hand healed this way. And then he had been too slow when he came back to work, and he was fired for being too slow, and then, now worked at a woodworking plant. And he had been working on the line building iPads. And I spoke with — when he told me this, I showed him my iPad, which had just come out right before I went to Shenzhen. And I showed him the iPad, and it was the first time he had seen an iPad in its completed state, because the people on the production line are often very carved off. Each step is very, very minute. The devices are very expensive, of course, and so they’re closely monitored. And so, no one has an opportunity to even handle them, in a way, really, outside of your individual step. And so, I turned it on for him and showed it to him, this thing that he had actually been maimed building. And it was his first time moving the icons back and forth. And he had a very human reaction, which is, he thought it was beautiful, you know? Which I think is understandable, because Apple does make beautiful devices. JUAN GONZALEZ: And Charles Duhigg, the actual working conditions at these plants, the hours that the workers work, the salaries that they make? CHARLES DUHIGG: It, by American standards, would be almost unconscionable. So, most workers inside the large plants — small plants are usually worse than large plants — but inside the large plants, they’re usually inside the factory for at least 12 hours a day. There’s some breaks in there. The shifts themselves are about 10 hours. But very often — and Foxconn says this isn’t accurate, so I need to caveat that, but our reporting indicates that it is — very often, people are asked to work two shifts in a row. So it’s not uncommon for someone to spend an entire day within a Foxconn plant. The amount that they earn, it’s a hard number to give, because the Chinese government keeps the currency of China low, so that it sounds — so that it sounds lower than what they’re earning. And it is a good wage. There’s a lot of — there’s a lot of people who migrate from villages into cities. They work for 10 years. They earn enough money that they can go back to their village and open up a small store or some other type of company. But by American standards, it’s $17 a day to $21 a day. And by American standards, it’s an enormously, enormously low amount of money. It is not a quality of life that we’ve become accustomed to. And it’s not a working condition that Americans would tolerate or that would be legal inside this country. • entire interview at Democracynow website

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11